Sorting through the boxes in my garage proved not only cathartic but enlightening and amusing.

There were new discoveries and familiar items that I hadn’t seen in years. As a kid I would sometimes thumb through my 2nd and 3rd great grandmothers’ photo albums which had been kept in my great grandfather’s glass bookcase. It was always fun to look at the crazy facial hair and kind of creepy photos of my ancestors. My dad would often point out that we had Hanks ancestors so we could be related to Abraham Lincoln’s mother. Spoiler alert, we aren’t.

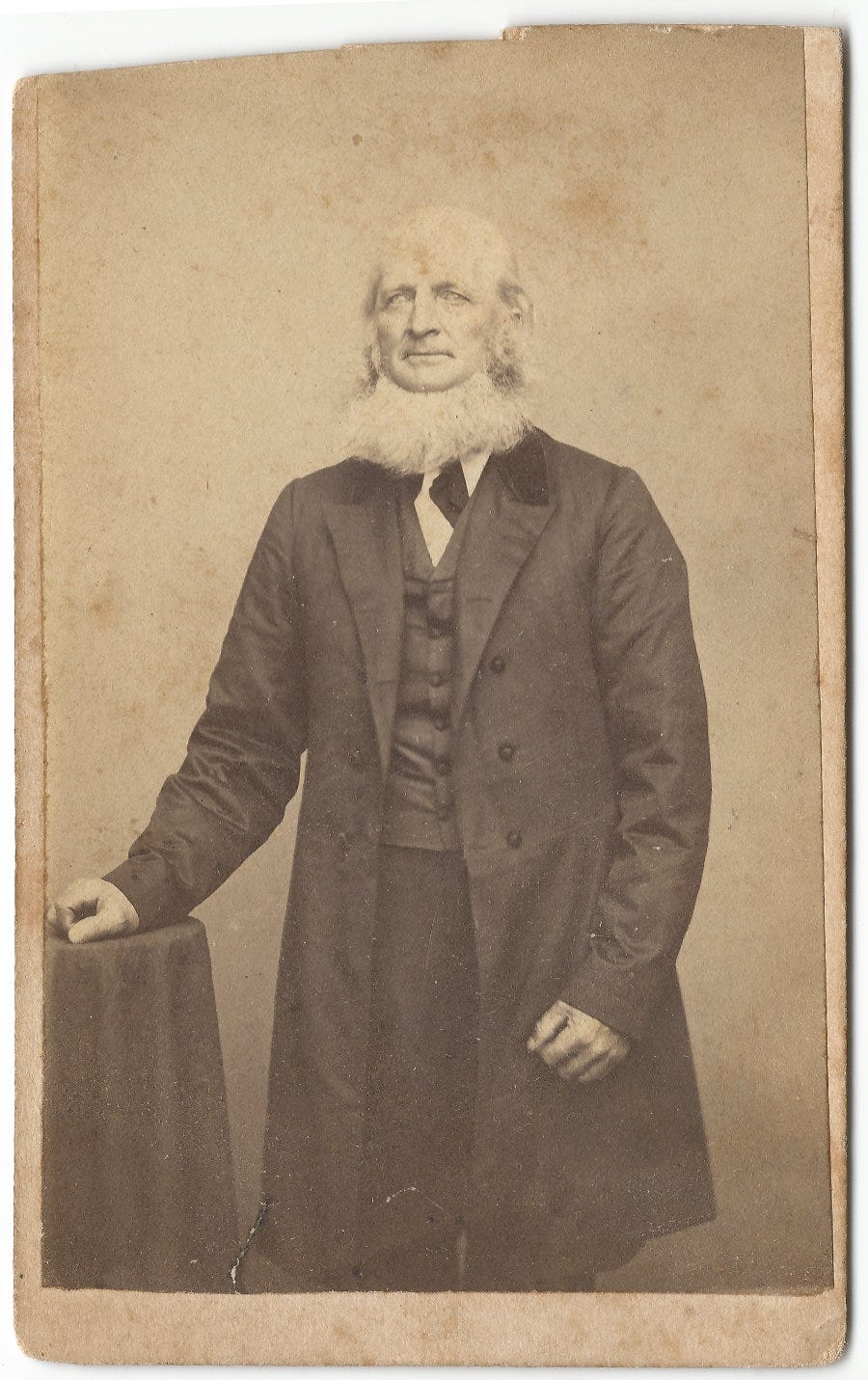

However, all those photos were of course studio portraits. Daguerrotypes, tintypes, cabinet cards and cartes de visite. Staid and rigid as the slow shutter speed cameras of the day demanded, the photos didn’t really tell me that much about them as people. My grandpa died when I was very young and he was an only child so much of what would have passed down had faded with time.

One of the few stories I did know was that of my 3rd great grandfather, Hendrick Gregg, who had been run over by a train in 1881. We still had his wallet and tobacco pouch and kept them in the drawer next to the bookcase. I would sometimes take out the mummified wad of tobacco to gross out my friends but wasn’t allowed to take anything out of the wallet because the contents were too fragile.

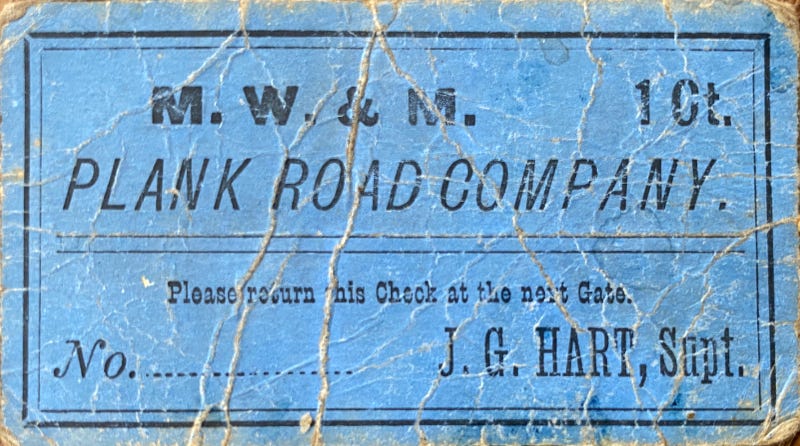

Now that I was a grownup I could do what I wanted so I carefully removed the contents of the wallet. It was full of receipts for things like a carriage and blacksmithing services, grocery lists with a variety of items including a sack of patent flour and a gallon of whiskey. There were also assorted oddities like a toll ticket for the Madison, Watertown and Milwaukee Plank Road and a note to Hendrick who was the “Overseer of the Poor” to “take care of this man Henry and charge to the town of Brookfield.” Some of them dated back to the mid 1870s. Apparently not cleaning out your wallet is a family tradition.

These ephemeral items which should have long ago been used to light a stove or, knowing my family, mark a page in a book, told me more about Hendrick than his studio portrait. It was a tangible, personal connection to him and his life which was ended so abruptly by the Madison Express.

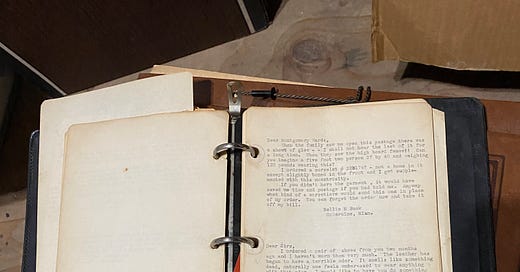

Examining the contents of the wallet made me think of the letter I had found from miss Helen Keith. The details of that letter had really brought her to life. Her youthful exuberance came through in every word. But there was also a sense of desperation, she was after all “in a hurry” for a response. She was writing to a catalog asking them to not only supply her with goods but for guidance on how to be a housekeeper and wife. Why was she going to a mail order catalog for that and not her family? Why was she moving to another country for a husband? The letter provided a glimpse into her life but also made me want to learn more.

I had already begun using Ancestry.com to research my own genealogy so I created another family tree for Helen. I was only able to find a few records at first. It wasn’t until much later that I was able to find a marriage record and get some answers, but more about that in a future post.

Having found at least something about Helen I started to think about the other letters. Helen’s letter was far from the only one which provided such intimate details of the writer’s life. Whether it was Gentry P McCorkle and others hoping to find love, or Helen Jesme sharing photos of her baby these folks weren’t just placing orders or registering complaints. They were looking for a connection. They were reaching out from places of isolation to someone they knew would respond.

As the letters became something more than amusing diversions I started to see the parallels to the situation most of us were living in at the time. When the world shut down in March of 2020, most of us retreated to the safety of our homes. We were driven to an isolation that was very foreign to our hyper-connected society. However, unlike the folks who wrote the letters in the 1930s we had plenty of ways to communicate with others. Every time I posted a letter to facebook or texted it to a friend I was reaching out as the original writers had done. I didn’t have to resort to tweeting Amazon for help with my love life or sending my baby pictures to ebay.

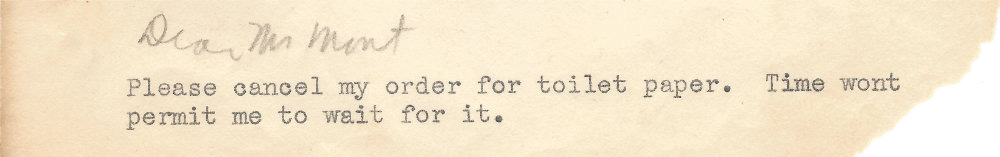

The similarities weren’t just conceptual either. The frequent references to toilet paper and its alternatives really hit home when I resorted to ordering a different kind of rolls with my takeout from local restaurants.

It seemed to me that I probably wouldn’t be the only one to recognize the connection between these letters and our current situation. So I finally decided to look into publishing them as a book.

The only problem was I didn’t know a damn thing about Montgomery Ward. I grew up in New England in a primarily JCPenney family with occasional dalliances in Sears and regional chains like G Fox, Bradlees and Caldors. I also needed more background on the letters and my grandma’s experience at Wards. So, I emailed my uncle and mentioned I was going to look closer at the letters and maybe publish them.

It turns out he had put together a presentation around the letters years ago that he had given at club meetings. Not only had he done some research on Wards he had interviewed my grandma and recorded it on audio cassette in 1981. He had the tapes digitized and sent them to me.

That’s when I heard my grandma’s voice for the first time since I was 10.

Next in Part 3: Verna tells her own story